Six Columns, One Search: Reconstructing the Word Through Language

Table of Contents

A Monumental Philological Act of Faith

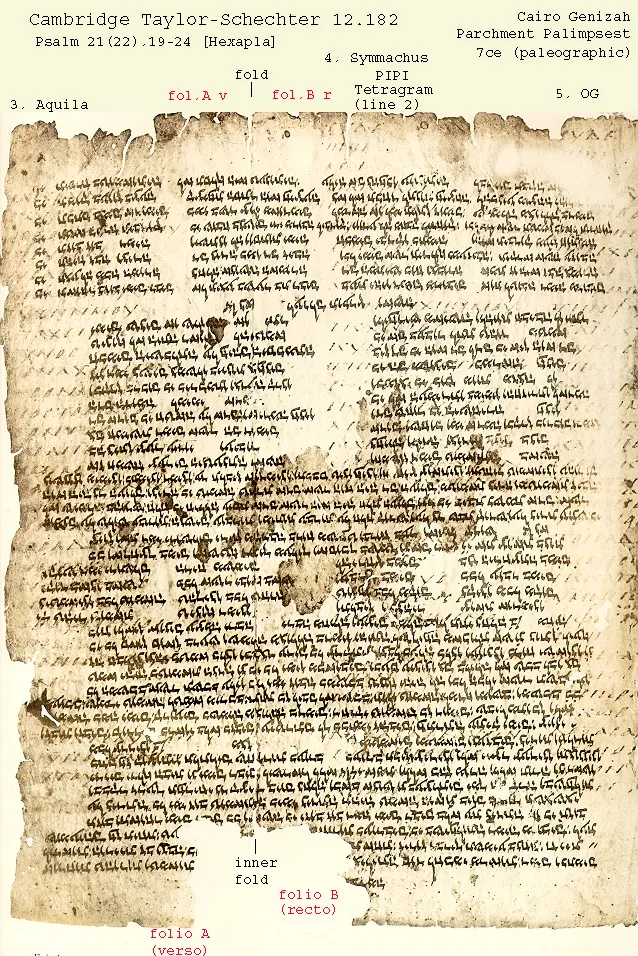

Origen’s Hexapla is not a book in the conventional sense. It is a massive comparative manuscript, created in the 3rd century CE, attempting to align and preserve multiple versions of the Old Testament side by side. Its name — from the Greek ἑξαπλᾶ — means “sixfold,” referring to the six columns of parallel text that made up the original compilation.

At the time, no standardized biblical canon existed in any single language. Hebrew texts, oral traditions, and a range of Greek translations circulated among Jewish and early Christian communities. Origen’s response was not to choose one over another, but to synchronize them in a layout that invited direct comparison and reflection.

It is one of the earliest and most ambitious text-critical projects in religious history — and arguably, an ancestor of all modern biblical scholarship.

The Structure: Six Columns of Comparison

The Hexapla was structured into six vertical columns, aligned line by line:

- Hebrew text in Hebrew characters

- Hebrew transliterated into Greek letters

- Aquila’s translation – hyper-literal Greek from a Jewish convert

- Symmachus’s translation – a smoother, idiomatic Greek rendering

- The Septuagint – the widely used Jewish-Greek version

- Theodotion’s translation – a Hellenized, revised version

Some books included even more columns (hence the occasional name Octapla, or even Enneapla), but the core project remains these six. The aim was not only to clarify textual variants, but also to defend the Septuagint — which was under attack by both Jews and Christians for being inaccurate or doctrinally dangerous.

Origen inserted critical signs — the obelus (÷) to mark additions, and the asterisk (*) to indicate restorations from the Hebrew — showing a methodical, almost modern precision in his editorial mindset.

What It Feels Like to Read (or Study)

One doesn’t read the Hexapla like a narrative — one studies it, decodes it, and listens for discrepancies. Even in its fragmentary state today (mostly preserved through citations in later Church Fathers, especially Eusebius and Jerome), the Hexapla exudes a scholastic rigor bordering on sacred obsession.

To engage with the Hexapla is to witness a deeply devout mind treating language as theology. Every word matters. Every vowel shift between columns is a potential doctrinal key. You begin to see scripture not as fixed, but as in formation — shaped by scribes, dialects, exiles, and centuries.

Origen’s genius lies not in originality of doctrine but in his methodology. The Hexapla is a working table — a proto-database — allowing comparison across linguistic traditions, helping readers discern where translation shaped theology, or where meaning shifted across languages.

Interpretation and Purpose

Origen lived in Alexandria and Caesarea during a time of theological ferment and tension between Jews and Christians. The Hebrew scriptures were foundational to both faiths, but disagreements over translation, especially regarding messianic prophecies, were fierce.

The Hexapla had three main goals:

- Apologetic Defense: Origen wanted to show that Christian readings of the Old Testament, particularly using the Septuagint, had textual legitimacy.

- Textual Clarity: By comparing different translations and inserting critical markers, he hoped to resolve inconsistencies and demonstrate the textual integrity of the Greek scriptures.

- Theological Neutrality (initially): Although deeply Christian, Origen approached textual criticism with a philologist’s restraint. He preserved Jewish translations with respect, even when they diverged from Christian readings.

There is something almost rabbinic in his reverence for textuality, despite his Christian allegiances. And that’s what makes the Hexapla so radical: it doesn’t simply assert truth — it compares it.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths:

- Groundbreaking example of comparative textual criticism.

- Demonstrates reverence for linguistic variation and textual tradition.

- Offers insight into early Christian scholarship before the rise of dogma-heavy orthodoxy.

- Preserves now-lost translations and fragments of the Old Testament.

Limitations:

- The original is largely lost. We only possess fragments and citations.

- Extremely technical; not suited for casual readers or even most students of theology.

- More a reference tool than a narrative or theological treatise.

Still, the Hexapla’s methodological legacy is profound. It teaches readers how to wrestle with the sacred through language, not just receive it passively.

Who Should Study It?

- Advanced students of textual criticism, biblical philology, or early Christian history.

- Scholars tracing the development of scriptural authority and canon formation.

- Readers interested in the theological significance of language, translation, and semantic drift.

- Anyone curious about the roots of modern biblical commentary, from Erasmus to today’s interlinear Bibles.

Final Thoughts

Origen’s Hexapla may be less known than Augustine’s Confessions or Jerome’s Vulgate, but it may be more foundational than either. It is the blueprint of intellectual humility in the face of sacred text. Rather than declaring what is right, Origen shows us how to search — across tongues, traditions, and errors.

Though most of the Hexapla is lost, its spirit survives in every scholarly apparatus, interlinear gloss, or footnote that dares to admit: the Word is old, and its path is crooked with human hands.

In a time when religious texts are often used to assert certainty, Origen teaches a different lesson: that reverence lives in the margins, and truth often emerges from juxtaposition.

TL;DR

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Author | Origen of Alexandria (c. 184–253 CE) |

| Method | Comparative, interlinear textual criticism |

| Structure | Six columns: Hebrew, Greek transliteration, Aquila, Symmachus, LXX, Theodotion |

| Skill Level | Advanced scholars, philologists, theologians |

| Teaching Style | Meticulous alignment, critical symbols, no narrative |

| Strengths | Textual preservation, interfaith relevance, scholarly innovation |

| Challenges | Mostly lost, extremely technical, hard to access without secondary guides |

| Best For | Biblical historians, Christian philologists, textual critics |

| Companions | Septuagint, The Jewish War, Jerome’s Vulgate, modern Hebrew Bibles |

| Verdict | A fragmented masterpiece that gave birth to critical scriptural scholarship |

Leave a Reply